[[{“value”:”

By: Travis Wayne

Loubna Mrie was marching up the hill in a sweeping blizzard in Vermont the first time I met her. Mrie’s first words: “I have bagels.” She handed us a large box of bagels she carried as an offering from a famous New York shop to our student organizing committee.

Mrie, then at New York University, had crossed state lines to be a guest speaker and workshop facilitator in the symposium we organized to connect students and domestic movement activists with Syrian revolutionaries in shared talks and workshops on organizing tactics. It was 2017.

In the pages of Defiance, bearing bagels becomes more symbolic: characteristic of a change in the definition of home that seems to represent a change for Mrie, who cracks jokes about “New Yorkers’ pride in bagels and their ignorance of what is happening on our side of the world” when she first arrives in the city. After surviving one soul-crushing loss after another in service of the Syrian cause, where the big tent popular movement led by civil society leaders and godfathered by long-term socialist thinkers like Yassin al-Haj Saleh was rapidly engulfed, ravaged, and co-opted in a liquid imperialist struggle between five colonial powers, Mrie realizes the extent of her loss with the acceptance of a new future:

“It is time for me to let go of Syria and consider New York my new home. This realization gradually helps me settle. I first notice that my mindset has changed when someone asks for my phone number, and I realize that I have it memorized. When people stop me for directions on the subway platform, I no longer avoid them and keep walking like I used to; now, I can give them an answer without a map.”

Loubna Mrie’s story is testament to one Syrian experience of revolution and exile, but its themes resonate on levels far deeper than the story of any given political struggle. Mrie’s memoir is a fiercely personal testimony of the human experience of surviving struggle itself. Despite far more hellish material conditions, organizers today can see in Mrie’s experiences ghosts of our own: displacements, resolutions, family losses, revolutionary relationships, political factions, half-homes seized from under you, political opponents with far more power, manipulators and opportunists, coping with the aftermaths of campaigns – and death. Over time, lots of death.

After describing the unique placement of the Alawite minority in the Assads’ governing political base, positioning her own lived experience within the social and political context of Syria on the eve of revolution, Loubna Mrie’s story ramps up in the household of a tyrant who lords over her household almost as much as Hafez al-Assad. “When we did everything right, we always seemed to have done something wrong” as Loubna and her mother chewed quieter and dodged phones flying just to keep the peace in the home. Abuse becomes clearer than the sun.

The shadow of Loubna’s father stalks the pages of the story far beyond the first ones. “My father’s ability to end lives was what had lifted him and his brothers out of poverty,” from an experience of the colonized working class of midcentury Syria to believing that “poor people are just jealous of us.” Following her family is to follow the story of the consolidation of a particular political rule in Syria. Mrie’s father’s violence becomes the commodified labor needed to transport social fortunes, for which her family is paid handsomely with vast estates of national wealth. Her uncle Wahib is just one beneficiary of Hafez’s rule when he becomes the Syrian “king of steel” overseeing hundreds of workers. Women in her family received next to nothing.

Joining an uprising – and thus rejecting her conservative background for the possibility of a new world – entails deep loss for Loubna just shy of twenty. As an Alawite organizer within the strategically big tent multiethnic movement, Mrie sits in rooms filled with smoke and photos of freedom fighters; argues against conservative intellectuals over whether the lower classes were too sectarian to be trusted with democratic rule; laughs with songwriters cutting their hair while recording songs mocking the military; and inspires, and is inspired by, movement journalists who believe that “documenting the government’s brutality … is the first step towards stopping it.” She organizes distros and pools funds for local civic organizing projects and blocks roads so “people at the intersection are forced to look, read, and witness the courage of the few:” observation and participation, bold action to inspire mass action. She hides her face with a scarf at meetings with ululations that shake the air as organizers blanket the mosques (each Friday, imbued with significance) as organizing spaces, public squares too highly policed.

As Mrie’s roles transitions within the movement she dedicates herself to, she goes out of her way to document municipal elections held against all odds, the first time in a generation for people to experience direct shaping of any aspect of their lives in what Syrian Communist Party (Political Bureau) leader Riad al-Turk called the Kingdom of Silence:

“The next day, Mezar and I join Monzer to film the election of the city council. Despite the constant air strikes, a few dozen people are gathered in a warehouse. They’ve bundled up against the cold and drawn their scarves tight over their heads. The air inside smells of fresh paint and exhaust from the diesel heaters burning in each corner. The windows are sweating, and the revolutionary flag is nailed to the wall behind the four candidates for office.”

Loubna eyewitnesses the noble spirit undergirding so much revolutionary activity. As she notices Kurdish migrant worker shoe shiners amidst the Syrian working class not visible within segregated urban enclaves, the mass action all around her against brutal repression inspires her to imagine new creativities to contribute to the new world:

“A popular chant around this time is for a city called Amuda, an iconic village in the Kurdish areas, but a town so isolated that most people have to spend some time searching for it on a map when they first hear the chant. Its protesters are famous for their signs that carry quotes and poems from the Spanish Civil War…

I want to go. I could shoot a short documentary, I think, showing how a small Kurdish town is teaching us, through their signs, about world history and the revolutions and poets of generations past.”

Like any organizer, critiques of her own movement sprout in Mrie’s mind with each successive month, year, campaign, lived moment. The Free Syrian Army (FSA) became so dependent on funders, Mrie notes, that they turned a blind eye on Turkish involvement in the kidnapping of their own founding leader – a complete loss of the soul of the militias, an early sign of their oblivion. She lambasts those that call for imperialist intervention out of desperation. Even though Gulf country funders “just want a Sunni government to replace the Alawite one,” the most cynical movement leaders trade everything for money. The Syrian National Council is an establishmentarian “hotel opposition,” ripped for “friending us on Facebook just so we can mock them,” while the exiled reduced to the status of Syrian refugee in the eyes of Europe are asked how “‘the revolution in Berlin’ is going.”

The nations expecting Syrian gratitude for basics are not spared Loubna’s wrath: “the Lebanon experienced by rich Syrians is not the same as the one experienced by the poor.”

Loubna also sees the personal horrors, how tragedy can destroy individuals in movement:

“It would take me years to understand that, under pressure, under the fear of death by execution, by torture, by bombing, people can release the monster they’ve spent most of their lives repressing. I didn’t know then that almost every marriage, every friendship that I saw blooming around us in Damascus during this time would die. The two couples that went to jail together and married right after they were released. The girl who was so scared her partner would be taken away by the police that she got pregnant just to preserve something of his smell. Or the girl whose boyfriend’s family rejected her because she was not Sunni, and who agreed to elope with him because the whole country was revolting against injustice, so why couldn’t they? Even Samar and her partner’s relationship would eventually collapse under the strain of exile and the guilt Amer was talking about. So many love stories. All of them decimated, just like our hopes of what Syria would become.”

Loubna copes with the loss of so many: so many lost friends, but also lost lovers – most brutally, Peter Kassig, a U.S. medical worker abducted by ISIS and executed by the fascists. Her partner’s murder isn’t the only one that carves a void into her life. Even movements can’t shelter us from the grief of survival, especially for someone like Mrie, who lost a whole world for a new one – only to end up lost, far from home, making a new home.

In the end, the killer that stalks the pages of Defiance from its beginning doesn’t just murder her mother who begs her to come home; he murders her dream of what home is, till she makes it anew. But the shadow in her family is not just her own, we learn, as one of many final horrors drop in the life of the organizer. When Mrie reveals rumors of Ba’ath Party founder and early leader Salah al-Din al-Bitar’s assassination, we see just how far the shadow could extend.

Defiance stands out because of its imagery: the kunafeh sizzling on copper plates, the wistful lanes of cities, its diligent documenting of the horrific spiraling of the Syrian Revolution beyond the control of any individual. But Defiance also stands out for its insights and foresights, where comrades who end up shot in the head warn of black flags replacing the green of the revolution and of a different kind of regime to come out of the black nihilism the movement descends into: a warning that foreshadows the massacres of Druze and of Alawites at the hands of post-Assad government actors and militias given implicit license to kill, as well as the assault on the socialist feminist autonomous zone of Rojava, which has (for now) averted all-out war in its stand-off with the consolidating state.

Read Defiance to dream, to cry, to feel – and to witness, through her own words, the experience of a fellow comrade who lost a whole world to win a world. Most of all: read Defiance, to survive and to fight, in spite of it all.

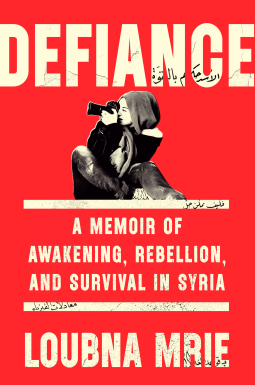

Defiance: A Memoir of Awakening, Rebellion, and Survival in Syria is scheduled to be published by Penguin Random House on February 24, 2026.

Travis Wayne is the managing editor of Working Mass.

The post Losing Your Whole World To Win a World – A Review of Defiance by Loubna Mrie appeared first on Working Mass.

“}]]