[[{“value”:”

By: Henry de Groot

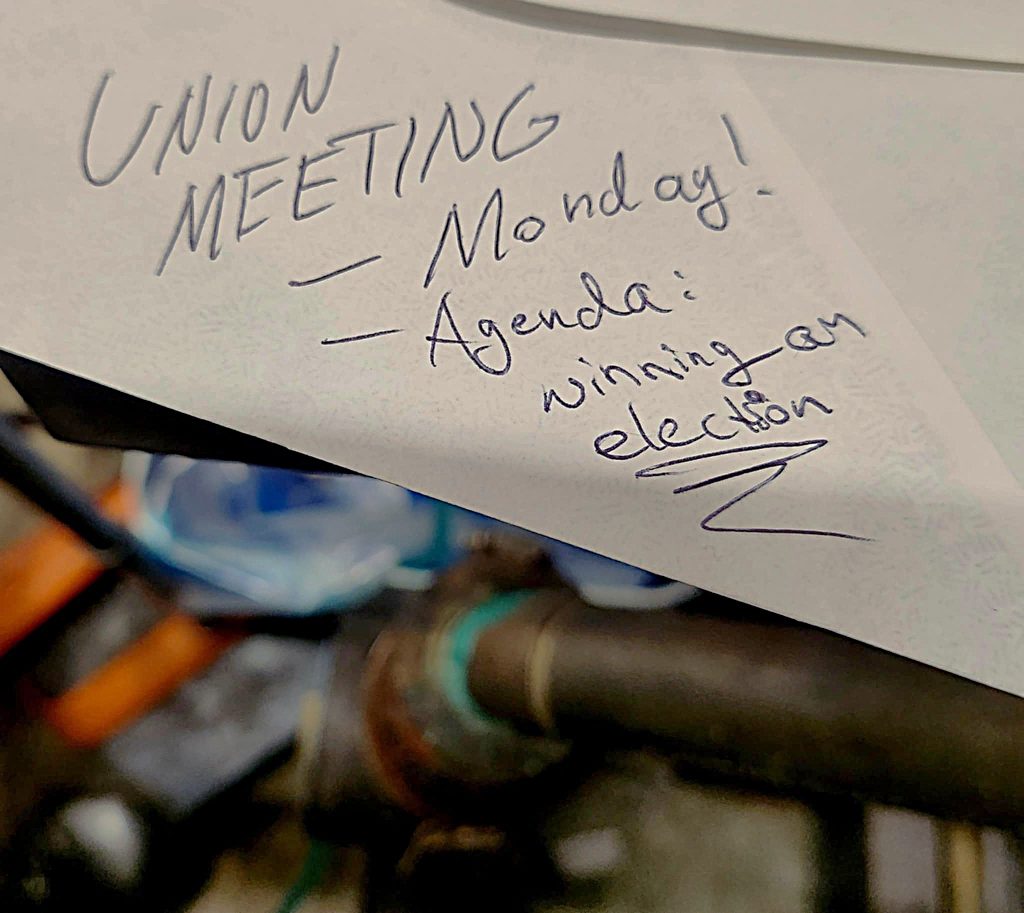

Henry De Groot breaks down how election campaigns can learn from organizing methods refined in the labor movement

Grassroots Campaigns Need More Than Mobilizing

Campaigns to unionize a workplace and campaigns to win public office may both involve voting, but often they feel like two worlds apart. And there’s a real basis for that – union campaigns are almost always in a ‘universe’ of a few thousand at most, if not hundreds or fewer. Meanwhile, election campaigns may need to span an entire country; even more modest races (for example, for state assembly) still involve multiple tens of thousands of potential voters. And if both can involve large budgets and fierce opposition campaigns, there’s no comparison in public election campaigns to the brutal intimidation tactics of captive audience meetings and closed-door interrogations that take place in union drives.

Campaigns for public office are tough, but the fight for control of the workplace is even tougher. And perhaps that’s why it has served as a crucible – a pressure chamber that has forced the development and codification of some of the strongest and most precise strategies and tactics for building power and beating one’s opponent. The typical difference can perhaps be summarized as a difference between organizing and mobilizing, two separate moees, to utilize the terms understood in the labor movement.

Most election campaigns are built to mobilize: campaigns tap existing networks for donations, identify supporters, persuade the movable middle, and turn people out on Election Day. That model can work, especially when campaigns have money, endorsements, institutional allies, and a mature voter file operation.

Union campaigns, if run well, focus on organizing: building long-term power by investing in the development of deep relationships. These investments build and maintain the durable trust needed to face down aggressive union-busting tactics and win. This high-cost, long-term investment makes sense in the union context, especially since the fight doesn’t end after an election victory but is often only the beginning. In many cases, securing a first contract requires taking strike action.

But grassroots campaigns for public office rarely have those advantages. They’re often running against deeper pockets and establishment machines, backed by the big money interests that want to protect the status quo. And, if they’re worth supporting, grassroots campaigns are also trying to do something harder than winning a single election: they’re trying to build durable power that continues beyond Election Day.

It is in this context that grassroots campaigns – those that see the need to organize – can benefit by drawing on the union methods of organizing, or what is known in the labor movement as structured organizing.

The Basis Of Structured Organizing

Structured organizing is a disciplined approach to building mass participation and leadership capacity. It combines a theory of power with concrete benchmarks and tactics, which are replicable across multiple campaigns.

The simplest and most powerful idea in structured organizing is also the most overlooked: people are already organized.

In a workplace, workers are already sorted into shifts, departments, buildings, job titles – and a workplace also has internal communities based on language, ethnicity, nationality, gender, as well as those based on social circles. These networks have norms, leaders, communication channels, and trust relationships.

Traditional campaigns often behave as if none of that exists. They build a campaign universe from scratch—email lists, volunteer signups, events—and then ask people to enter that universe. The people who do are often already politically comfortable, already connected to movement spaces, or already inclined toward volunteerism.

But since trust is the fundamental variable for the strength of an organized community, this misses a huge opportunity to tap into existing trust and to unite it with the campaign’s ends.

Instead of expecting people to join your structure, in a structured organizing approach you build a campaign structure that parallels and taps into the structures that already exist. It’s like scaffolding built around real life. And because it’s built around what’s already there, it can go deeper, faster, and with more legitimacy than a campaign trying to manufacture community in real time.

This is one reason structured organizing is so powerful for grassroots campaigns: it lets the campaign leadership access trust it didn’t create but can respectfully earn the right to participate in.

The Key Concepts of Structured Organizing

Understanding that a community is already organized, we can then deploy a set of tactics in order to build a structure which taps into the existing networks. The following practices work towards that and reinforce each other, and the strength of the approach comes from the way these parts fit together.

1) Mapping Existing Networks, Identities, & Affinities

The first step to tapping into the existing ways in which a community is organized is to ‘map’ that community. And mapping a workplace or an election landscape is not so different.

First, the campaign team begins by noting all the various segments of the population. In an election campaign, this can be: geographies, ethnic demographics, issue-based networks, and the various existing communities like unions and environmental groups active in the area.

Then the campaign considers each group both qualitatively and quantitatively. What key role might each group play in the campaign? What unique strengths might they have? And how large are the populations of each group relative to the overall campaign universe?

Finally, a campaign can note what existing relationships it may have with each group and identify gatekeepers and influencers, who can help provide access and inroads into the community.

The same process can be run on the campaign’s own supporters. Supporter surveys, which collect this kind of data about those who sign up for the campaign, can help to reveal how much progress the campaign is making in tapping into the networks and communities that it has mapped. In addition, the campaign can collect information about its own unique network: those willing to help volunteer, be it on canvassing, fundraising, phonebanking, or volunteering on a video or social media team.

2) Organic Leaders

Every network has people who function as hubs. Often they don’t have official titles, and they may not be the most politically involved or ideologically motivated. But they are the people others already trust—people who can convene, interpret, and legitimize.

Organic leaders are the key access point of the campaign in engaging its target communities. By prioritizing the identification and engagement of existing organic leaders, the campaign secures its engagement with each community.

And the campaign need not rely only on existing known community leaders. The campaign can also help develop members of its target communities into leaders of that community in relation to the campaign’s efforts. Even if someone is not already a recognized community leader, just being part of a community gives them a level of trust and insight that can serve as a huge advantage relative to someone from outside that community. When demographic and affinity data is tracked at the same time as the campaign tracks levels of engagement (see below), this creates an easy matrix through which the campaign can identify and develop highly engaged members of each community.

The strategy is simple: the best people to organize a community are those from that community.

3) Representative Leadership Committees

Candidate platforms typically highlight where a candidate stands on key issues. And traditional campaigns spend time interfacing with the communities they see as key to building a winning coalition, making sure those communities feel heard and included in the campaign.

An organizing approach goes deeper: instead of simply listening to these communities, an organizing approach facilitates members of each community to help shape the engagement of that community.

Something as simple as hosting a committee meeting can turn supporters into organizers. In these meetings, a campaign organizer hosts the space and invites the participants (i.e., community members) to help the campaign develop its messaging as it relates to their community needs. And they work to consider how they can engage their peers. As ‘locals,’ these participants often have far greater insights and relationships in the target community than does the facilitator.

These committees can help draft sign-on letters, take on lists of the fellow community members for phonebanking, or plan an affinity-based fundraiser. Not only does this help to get work done, but it also makes these supporters feel ownership of the campaign. Hosting these committees weekly or bi-weekly is a great way to develop a collective organizing team that takes responsibility for leading the campaign’s efforts in a key community.

When supporters feel ownership over the campaign they are willing to give far more of their time and effort. And similarly, when folks organize in their own community, they are likely to be far more effective than if they take up general volunteer tasks.

This system assumes that the campaign is comfortable campaigning in a genuinely democratic way and willing to make long term investments. Building committees may not be the fastest way to produce results in the short term and requires navigating potential differences both within a committee and between that committee and the campaign/ its candidate. But the long-term benefits outlined above make this strategy worthwhile.

4) Building Distributed Organizing

Most grassroots campaigns fail not because they lack supporters, but because they do not adequately engage their various layers of supporters and relate these layers to each other. Everything funnels through a few staffers or a handful of super-volunteers. It is simply not possible to grow a campaign into a mass movement in this way.

The only possible way to build a mass campaign which does real organizing at scale involves the core team’s focus on developing a middle layer of volunteer leaders. And this is not the same as simply having the core team train volunteers to engage directly with the public. Rather, what is necessary is to train volunteers as organizers – those who can manage and lead other volunteers.

To facilitate this process, campaigns need to build an ideology of organizing into their self-conception, and ideally into their self-presentation as well. Then, the campaign should invite supporters to take responsibility and should provide some initial training. A simple training focused on encouraging supporters to share their personal stories is often a sufficient starting point, with additional coaching and support provided after volunteer-organizers get underway.

Then, volunteers are assigned lists, usually for phonebanking. Two basic tactics can be used for list work.

First, volunteers can be given lists to make “assessment calls.” These are first-contact calls with supporters, where a volunteer-organizer conducts a brief story-sharing exercise to drive further engagement and assess the interest of that person to get further involved. The volunteer-organizer should track data and take notes for subsequent follow up. One very helpful tool at this stage is a simple supporter survey (the same one sent out by email). Volunteer-organizers often talk too much, listen too little, and don’t collect the desired information. By its nature, a supporter survey guides a volunteer-organizer an opportunity to listen and collect data.

Second, volunteers may be given a more permanent list, which they are responsible for organizing over the long term. In this system, volunteers engage and re-engage their list, focusing on long-term engagement over short-term turnout. Often, this list is composed of those who have already had an assessment call and have already indicated their interest in volunteering on the campaign.

This is a great time to cut and distribute lists based on target communities. Phonebanking a general list of potential supporters can feel painful and endless. But give a nurse a list of 100 healthcare workers, or an educator a list of 100 fellow teachers, and they will amaze you with their enthusiasm, creativity, and perseverance. Establishing among volunteers an understanding of the impact of their efforts is profoundly important to a campaign. And when volunteer power is the main resource of a campaign, the difference is life or death.

It is also possible to combine these two methods, so that a volunteer is given a list that includes both unassessed and assessed supporters, with the volunteer responsible for managing the entire list for the long term. This system is usually applied to lists cut geographically, because by definition the campaign will generally not know where else to assign unassessed persons if they don’t have data on their union, demographic, or issue priorities. In this case, the volunteer understands that they are responsible for taking charge of a given neighborhood or town.

5) Structure Tests: Strength Comes From Use

In structured organizing, the aspiration is to build a campaign that maps onto the existing structures of our organizing landscape. But what matters is not whether the campaign’s ‘scaffolding’ looks or appears to model and provide access to these networks, but whether it actually does.

It is only by using our campaign structure that we can test whether we have built the true ability to activate our targeted communities or not. And furthermore, the depth of trust that we need to build is not built one-off, but iteratively through struggle and use. ‘Structure tests’ refer to the ways through which we can test out our campaign structure as we go, measuring whether we have built the strength necessary to escalate our work, and revealing gaps which we need to address.

In a structure test, you deliberately ask the structure to do something real and measurable so you can see whether it holds.

Probably the first and most useful use of a structure test for a campaign is to test the volunteer layer. A campaign which wants to grow and create a distributed organizing system may be inclined to rapidly assign titles and responsibilities to volunteers – but these are much easier to give out than to take back. Unfortunately, many volunteers who appear motivated or talk up their willingness to build the campaign end up falling short of delivering on their commitments.

A campaign is best served if the work is given out before titles, running a structure test in miniature on each volunteer to see whether enthusiasm actually translates to work ethic and results. If a volunteer wants to take a lead in a neighborhood, give them five or ten numbers in their area, and see how far they get. This also serves as a great opportunity to provide follow up coaching and training, which is often more useful after someone has actually dipped their toes in the work.

This can be replicated at a higher level. Instead of putting some volunteer in charge of overseeing other volunteer-organizers right away, give everyone their own area of work. The most capable and motivated organizers will make themselves apparent and can be relied upon to help lead their peers.

The same can be true of volunteers with special skills. Someone interested in video production may have grand ideas about what can be produced. But the sooner the campaign can assign them a concrete piece of work, even if small, the sooner the campaign can separate serious volunteers from the unserious.

6) The Organizer’s Bullseye: Prioritize Leadership Development

The final framework to note on structured organizing is perhaps the most basic and fundamental: the organizer’s bullseye.

Many campaigns treat organizing as “more volunteers,” but the real catalyst for growing a campaign is securing more leaders.

The organizer’s bullseye is a well-established framework for categorizing supporters into their levels of involvement in the campaign, with the core team at the center and the passive sympathizers at the edges.

The bullseye framework reminds us that every supporter can become a leader and challenges us to bring as many of our supporters as possible into our core leadership team. At the same time, it recognizes a ladder of engagement, and invites us to focus on bringing each group in towards the center one step at a time. Sympathizers can become supporters, supporters can become volunteers, volunteers can become organizers, and organizers can become parts of the core team.

Not only can the campaign apply this model in general, but it can also be applied within each campaign community, as discussed in the section on building organizing committees.

How Video Can Supercharge Your Structured Organizing

In today’s campaign environment, video has become an essential part of reaching voters. But video can also be a key tool in organizing – motivating your volunteers, helping you reach and develop organic leaders, and helping you drive engagement with target communities.

First, engaging supporters as ‘spokespeople’ by recording videos with them can be a great way to make use of your volunteer potential. People connect with personal stories, and when you highlight the stories of your supporters – how they’re impacted by an issue, how it affects their community, and their organizing alongside your candidate to make a difference – your campaign gets to amplify their story alongside your candidate’s personal story. And right away, by capturing and sharing a supporter’s story, you often turn them into a super-volunteer.

These videos can then be used to engage in structured organizing.

First, the videos can be shared externally, posted on social media, or run in targeted ads, which reach other members of the speakers’ community. This additional trust gets you closer to building relationships with potential supporters.

Additionally, the videos can be used internally. By sharing the videos among your existing supporters, especially in a micro-targeted way, the story of your new spokesperson can help to drive deeper engagement and motivation among their peers who already support your campaign.

Organizing is about building trust through sharing our stakes and lived experiences. And when we capture our supporters’ stories on video, we can deploy them at a scale far greater than what is possible on the doors or through phonebanking.

Raising Funds To Fight

Every campaign needs funds, and structured organizing methods can also be helpful in driving up fundraising numbers.

At the most basic level, a campaign which drives deeper levels of engagement and builds real, personal relationships is going to raise more money from its supporters. But we can also fundraise in a specifically structured way, by utilizing the networks and relationships that our structured organizing methods have helped to develop.

One opportunity is to break down fundraising into geographic or affinity group-based appeals. A campaign that collects data on its supporters can deploy micro-targeted fundraising appeals that are tailored with the messaging most likely to resonate with the target community. And better yet, feature a video appeal from one of the communities’ members.

If someone receives a donor page tracking a donation target for their own neighborhood, they are not only more likely to donate, but they may also share that page with other activists who live nearby. Similarly, a union member is likely to contribute more to a donation page which tracks union member donations, because they feel a pride in the union movement and an obligation to live up to that movement’s values.

For the same reasons, distributed organizing can be utilized to drive donor phonebanks. A union member will not only be more willing to call other union members to ask for money, but they will likely also be more successful than calling a general list. And for the highest impact, these appeals will be done by those volunteer-organizers who have already been building long-term and deep relationships with the lists they are calling for donations.

Again, structured organizing maximizes results because it provides greater significance and ownership to both volunteers and sympathizers about the impact their support can make.

Organizing Transforms Us For The Better

Progressive campaigns are tough. Taking on corporate-backed candidates means grinding out an uphill battle. And good policies and good vibes are simply not enough to win. What is needed is the maximization of people power, the maximization of collective struggle, which can be brought to bear in support of the campaign. Structured organizing provides a scientific framework to organize for that power and win.

But each election campaign is just one piece of our larger fight against the capitalist system. When we run campaigns based on structured organizing, we develop leaders and bring together communities which can make an impact beyond election day. We transform our campaigns from efforts to win elections, into propaganda and training vehicles for the kind of collective organizing that we need to win not only at the ballot box, but on the shopfloor, in our neighborhoods, and in the streets.

The post How Structured Organizing Can Help Win Elections appeared first on Working Mass.

“}]]