[[{“value”:”

An Argument for a Permanently Expanded Social Safety Net

By Matthew Erlich

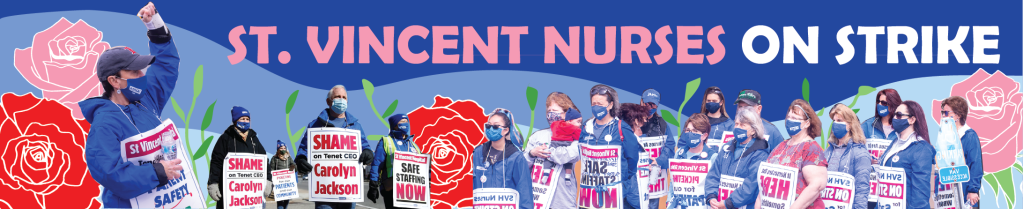

With news breaking on April 22 that the Massachusetts Nurses Association and Tenet Healthcare will be resuming talks in the coming days, after prolonged stalemate, it’s worth reflecting on a key development that may have played a role in forcing the company’s hand.

On April 9, the striking nurses of St. Vincent Hospital in Worcester received word that the U.S Department of Labor had confirmed striking workers would be eligible for COBRA subsidies. A week before that on April 2, a major hurdle was cleared in the process of obtaining unemployment insurance (UI) for the striking workers. This means that striking nurses who walked off their jobs 7 weeks ago to demand safer staffing and patient care in the hospital have been provided with a guarantee of affordable health insurance and the expectation that expanded unemployment benefits are in the pipeline as well.

COBRA, or the Consolidated Omnibus Budget Reconciliation Act of 1985, mandates employers who provide health insurance to their employees in which those who lose their employment due to a “qualifying event” an opportunity to buy into an extension of their insurance. Unfortunately, the out of pocket costs of COBRA are often prohibitive. However, when the American Rescue Plan (ARP) was passed earlier this year, it included a subsidy to help qualifying workers at risk of losing health insurance pay for COBRA, as well as a monetary increase in UI payments. Under Massachusetts state law, unemployment due to a labor dispute qualifies for UI if the employer continues to operate at greater than 80% of its normal business. In addition, when the Department of Unemployment Assistance (DUA) determines a claim to be eligible, the employer has 10 days to respond. Unsurprisingly, Tenet Healthcare (St. Vincent Hospital’s parent company) prolonged the process as long as possible. Although they opposed UI benefits for their workers, Tenet confirmed that they were indeed operating at greater than 80%, thanks to the millions of dollars being spent on strikebreaking replacement nurses.

Bill Lahey, a nurse in the endoscopy center, has been at St. Vincent for 44 years and was active in the original strike for union recognition in 2000. “I was ecstatic,” he says, when he learned of the decision that the COBRA subsidies would apply to workers in a labor dispute. “They’re up against a wall. So any little thing like this was gonna help them…These are my fellow nurses!”

In addition to the boost in morale provided by this news, Lahey recognizes the strategic implications of COBRA and UI as well. “It will solidify our position, we will not be bent, we will not be broken.” Lahey’s prescient words came just a few days before the announcement that talks would be resuming.

So what role have these reinforcements played in fortifying the nurses for a long fight against one of the largest for-profit healthcare operations companies in the country? At the core of the strike is a longstanding history of a tightly knit workforce dedicated to one another and the service of their community.

And yet, facing off with a behemoth like Tenet capable of spending an estimated $33.5 million per week on replacement nurses and police details is daunting, even in the face of powerful solidarity.

While there is no doubt this strike has proven extremely costly for Tenet, it pales in comparison to the toll on the striking nurses who still must pay their rent or mortgage, buy groceries for their families, deal with unforeseen healthcare costs or any of the other litany of costs associated with living under capitalism. In his book The Three Worlds of Welfare Capitalism, the Sociologist Gosta-Esping Anderson writes that “When workers are completely market-dependent, they are difficult to mobilize for solidaristic action.” A safety net turns basic social and economic needs into guaranteed rights, removing them from their reliance on the market. This, Anderson explains, “strengthens the workers and weakens the absolute authority of the employer. It is for exactly this reason employers have always opposed [this].”

Put simply, the link between a strong safety net — one that ensures access to healthcare and income for people out of work — is a crucial component to leveling the playing field between working-class people and a Fortune 500 company (Tenet reported $414 million in profit last year). Conversely, a weak safety net is a tool employers use to discipline against work disruption. The choice to collectively withhold labor is the ultimate bargaining chip workers have, but people do not make the choice to go all in without seriously considering the risks. The immediate consequences of a work stoppage must be weighed against the expectations of what can be achieved through collective action. No matter how underpaid, poorly treated, or unsafe your workplace is, facing the prospect of losing health insurance for yourself and your family, or the ability to cover expenses, it makes the choice to take collective action that much more difficult.

It is not a coincidence that the decline of labor and the decline of the safety net have coincided with the rise of neoliberalism over the past 40-plus years. This was after all a political project that began with attacks on labor, then set its sights on rolling back welfare programs and cutting the taxes used to fund them. The result has been unions falling from peak representation of 35.7% of the private sector workforce in 1953 to just 6.2% in 2019. The previously merely inadequate safety net has slid into near non-existence over this same period: in 1979, 82% of poor families received direct cash assistance, dropping to 68% by 1996, to just 21% in 2019. Insufficient unemployment benefits often discourage workers from filing claims even when they do qualify. Our current unemployment insurance system is outdated, underfunded, unwieldy and has failed to evolve with changes in the labor market. If one examines differences in state by state generosity, they will, unsurprisingly, find that the states with the least generous benefits are amongst the states with the lowest union density and most hostile labor laws.

In this context it might seem almost inevitable that there was a decrease in strike activity from a peak in 1974, when nearly 1.8 million U.S workers were involved in work stoppages to a nadir in 2017, when that number was a mere 25,000. But a recent uptick in 2018 and 2019 when over 400,000 workers walked off their jobs in each respective year, suggests a renewed appetite for labor action–and actions like the St. Vincents’ nursing strike points to a way forward for even more collective action by workers.

It should not be overlooked that although the ARP represents an important boost for worker leverage, it is flawed in many important ways. First, it is temporary, with the expanded UI benefits expiring September 6, 2021 and the COBRA subsidies expiring September 30, 2021. It also does nothing to change the state-by-state provision of UI. This means that the additional benefits get added on to the highly variable disbursements of a given state, with Massachusetts having a maximum benefit of $1,236 per week and Mississippi’s being a meager $235 per week (neither of those figures include the $300 in expanded benefits currently available as a federal government subsidy). Furthermore, while the COBRA subsidy has enabled countless people (like the striking nurses at St. Vincent) to retain affordable health insurance, it is a deeply inefficient way of doing so and represents a massive cash transfer to private insurers.

Nevertheless, we should not ignore the very real role these changes have made in the ability of the working people, who make our society run, to stand up for themselves in their workplaces with the knowledge that there is indeed a safety net to catch them. Imagining a revitalized labor movement should also involve imagining a revitalized safety net that makes permanent, and goes beyond, the very welcome help provided by the ARP. Unemployment benefits should be permanently made more generous and should be administered at a federal level. Healthcare must be universal for all people and should not depend on things like employment or immigration status. Just as there has been a vicious downward spiral of a weakened labor movement and eroding welfare state over the past 40 years, in reversing this trend we can create a positive feedback loop, in which a stronger labor movement also leads to a more robust safety net.

As the nurses of St. Vincent Hospital bravely fight against a company deadset on putting profits over their patients and the frontline workers who care for them, we are witnessing the tools that a stronger safety net gives David when the time comes to fight Goliath.

Matthew Erlich is a member of BDSA’s Labor Working Group.

“}]]