[[{“value”:”

As Steward Health Care Faces Acute Crisis, A Pattern of Favorable Regulatory Rulings and Large Campaign Contributions to the Attorney General’s Office Raises Optics Of Quid-Pro-Quo

By Henry De Groot

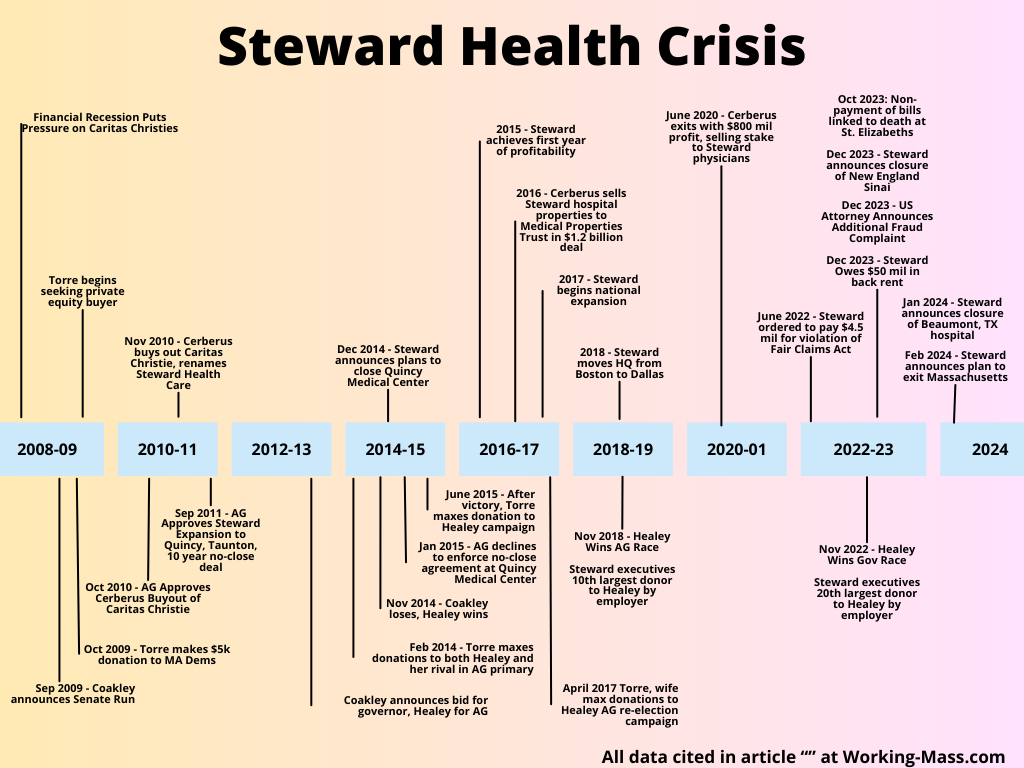

Steward Health Care in Crisis

When Steward Health Care announced in early December that it would close New England Sinai Hospital in Stoughton, Massachusetts in the spring of 2024, it was not immediately obvious that the closure would be part of something bigger. But then a mid-January expose in the Boston Globe raised the threat of a full-blown crisis, highlighting the company’s closure of one of its hospitals in San Antonio, Texas in May of 2023 with only two months’ notice, and the company’s $50 million debt to its landlord for late rent payments.

Then in late January Steward announced it would close its hospital in Beaumont, Texas with only one week’s notice, seemingly confirming that the company was in fact in financial crisis. Since then additional reports from vendors have come out showing that the hospital network has failed to pay its bills. The crisis has disrupted the network’s ability to keep services operational, and led to the suspension of construction at its Norwood facility.

The hospital network is the largest physician-owned for-profit hospital network in the country with 33 hospitals across several states. Steward operates 9 hospitals in Massachusetts, including St. Elizabeths in Brighton, Carney Hospital in Dorchester, and 7 other hospitals in Eastern Massachusetts which largely serve working class communities including Fall River and the Merrimack Valley. In addition to its hospital division, the company also operates a primary care network and a specialty provider network, as well as a Steward Health Choice, a Masshealth insurance plan. Former Speaker of the House John Boehner is one of its 7 board members.

Many have drawn attention to the contrast between the dire conditions of the hospital network and the luxurious lifestyle of its CEO, Dr. Ralph de la Torre.

At least one death has been attributed by the Boston Globe to the company’s financial issues. In October of last year, a patient experienced internal bleeding the day after giving birth to a child at St. Elizabeth’s in Brighton. When surgeons sought to use an embolism coil to induce a blood clot to stop the patient’s bleeding, the staff found that the hospital’s supply of the devices had been repossessed by the supplier because of nonpayment.

Additionally, the fate of 16,000 union and non-union Steward employees in Massachusetts and the hundreds of thousands of patients they serve remains precarious and uncertain, as the company may at best sell off or at worst close down some or all of its facilities. Steward employs thousands of union workers affiliated with SEIU 1199 and Massachusetts Nurses Association.

In contrast to his struggling hospital system, CEO Dr. Torre has been living his best life. After highlighting the CEO’s $40 million yacht, Aramal, which is currently moored in the Galapagos Islands, Globe columnist Brian McGrory had to issue a correction, having missed the CEO’s other yacht, a custom built, $15 million, 90 foot long sportfishing vessel, Jeraco, which some have called the “most ambitious sportfish boat ever built.”

In a later column McGrory continued his exposure of Torre’s lavish lifestyle, highlighting his travel in the Steward-owned Bombardier Global 6000. The plane costs $62 million new, and is the same model used, controversially, by popstar Taylor Swift. Steward also operates a Dassault Falcon 2000LX. McGrory reports that he tracked the Bombardier Global 6000 to “Santorini, Corfu, Athens, Naples (Italy, not Florida, but Florida, too), Madrid, Rome, Croatia, and the French Riviera,” as well as “the Bahamas, St. Kitts, Cabo San Lucas, Providenciales, Montego Bay, St. Maarten, and Antigua.” According to McGrory, both planes have been listed for sale in the past week.

MA Politicians Put Pressure On Steward

As the crisis has developed, Steward has faced increasing pressure from public officials. In a mid-February statement Governor Maura Healey expressed concerns that the crisis could lead to potential closures, layoffs, and disruption of healthcare services in the Commonwealth. Last week, Healey escalated her pressure in an additional statement, demanding financial disclosures and that the hospital exit the state; the governor also opined that “we don’t have enough [information] to know what they’ve done, whether it’s criminal or illegal, but to me it really smells, it raises a lot of questions.” The hospital network has confirmed it intends to transfer ownership of its Massachusetts hospitals.

The Commonwealth’s entire all-Democratic congressional delegation issued a letter earlier this month to Cerberus Capital Management, the private equity firm which established Steward Health Care as a for-profit entity in 2011 before selling its stake, to inquire about how much profit the firm made from its involvement in Steward.

The Looting of Caritas Christie and the Birth of Steward Health

The Boston Globe and other outlets have already explored the role played by private equity looters in the formation of the crisis, but it is worth summarizing here.

Although now headquartered in Dallas, Steward has its roots in Massachusetts in the Catholic-owned Caritas Christie hospital network, which was previously New England’s second largest hospital network. After the financial crisis of 2008, Caritas Christie faced financial insolvency, and was apparently unable to secure acquisition by a non-profit or larger Catholic-run hospital network.

Instead, Caritas Christie CEO Dr. Ralph de la Torre organized a $246 million buyout of the Catholic hospital network by Cerberus Capital Management, a multi-billion dollar private equity company with a broad set of investments, with Shaws, Star Market, Safeway, and Albertsons being among the best-known.

Cerberus secured regulatory approval for its 2010 buyout of Caritas Christie, and then, as pre-approved by government regulators, revoked its non-profit charter and converted the hospital chain into a for-profit subsidiary, changing the name to Steward Healthcare but keeping Dr. Torre on as CEO of the new for-profit entity. Cain Brothers, the advisory firm brought on by Caritas Christie to facilitate the buyout, was awarded a Deal of the Year Award by Investment Dealers’ Digest (IDD), “the insiders guide to investment banking and capital markets.” Reviewing the deal in an article “Nonprofit? Not Anymore,” IDD highlighted that “a not-for-profit hospital system had never before gone through a conversion and been sold to a private-equity firm.”

Cerberus secured Steward’s first profitable year of operation in 2015, and in 2017 began expanding around the country, for a time holding the mantle of the largest for-profit hospital corporation.

According to physicians familiar with the practices of Steward Health hospitals, the chain began operating on an “eat what you kill” model based on “relative value units,” in which physicians receive only a nominal salary and instead receive the majority of their compensation based on the number and type of procedures which they perform. According to some, this commission-based compensation system can lead to physicians focusing on profitable procedures rather than the best interests of their patients. Indeed, in 2022 Steward Health was ordered to pay $4.7 million for violations of the False Claims Act as part of a pay-for-referral scheme, and the US Attorney’s Office issued an additional complaint at the end of 2023 for separate violations of the Physicians Self-Referral Law related to over-billing of Medicare patients at St Elizabeth’s.

An insurance administrator involved in the development of Steward Health Care’s insurance offering, MassHealth plan Steward Health Choice, opined to Working Mass that the product was essentially a vanity project for Steward’s leadership.

As private equity firms tend to do, Cerberus then sought to engineer its profitable exit from Steward. It began this process in 2016 by selling off its hospital buildings to a real estate company, Medical Properties Trust, for $1.2 billion, which then leased the facilities back to Steward. These transactions allowed Cerberus to pay off the debt it had acquired from the initial $246 million buyout of Caritas Christie, although in doing so saddling Steward with a new rent burden.

Cerberus then finalized its exit in 2020 by selling its ownership stake to Steward’s physicians, converting Steward into a physician-owned hospital (POH) network. Although a POH network may seem like a more equitable and appropriate ownership structure than a ownership by a private equity firm, it is possible that Steward physicians were sold a bad deal on the vision of becoming collective owners, “holding the bag” after Cerberus had looted the network by liquidating its real estate. The doctor-owners were left with a company which now had to pay rent to use its own facilities, undoubtedly weighing on the companies financial health.

How The Attorney General’s Office Empowered The Rise of Steward Health

While the capitalist conversion (read: looting) of the non-profit Caritas Christie into the for-profit Steward Healthcare summarized above has been thoroughly explored in other outlets, what has not been explored is the role of Massachusetts Democrats – and particularly those associated with the Attorney General’s Office including Martha Coakley and now-governor Maura Healey – in facilitating this looting, and pocketing donations from Steward executives..

At the time, the buy-out of a non-profit hospital by a private equity company was unprecedented, and required approval from the Attorney General’s office. Then-AG Martha Coakley approved the transaction in 2010, finding in a report that all potential conflicts of interest had been sufficiently addressed, including by noting that “in light of his potential future employment by, and board service with Steward, Dr. de la Torre, Caritas’ President and Chief Executive Officer, abstained from the March 19, 2010 vote by the Board to approve the Transaction.”

It should be obvious that a CEO who actively organizes and campaigns for a buyout does little to negate this impact by abstaining from a final vote. And with hindsight it is also obvious that doctor, CEO, and yacht-enthusiast Torre has benefited tremendously from securing the buyout of Caritas Christie. The combination of the current financial crisis at Steward and the financial fortunes of Dr. Torre seriously calls into question whether the Attorney General’s Office met their requirement to defend the public interest in approving the 2010 transaction.

Coakley further extended her grace to Steward Health the following year, allowing them to buy out an additional two hospitals in Taunton and Quincy. Although Coakley’s approval came with a agreement that Steward would not close either hospital for at least 10 years, Steward announced it would close the Quincy facility in 2014 just days after the 2014 election. In January while still in office, AG Coakley waived the state’s right to sue, instead negotiating that Steward would keep open the hospital’s emergency facility for an additional year, and enter into a monitoring agreement. As Healey was already AG-elect, it is not clear whether Healey or Coakley was the decision maker in this sweetheart deal. Either way, just one year later in 2016, despite being under this monitoring agreement overseen by Maura Healey’s AGO, Steward was allowed to sell its properties, including the Quincy and Fall River properties, to Medical Properties Trust, undermining the hospital network’s financial position and thereby healthcare services in the Commonwealth, and obviously laying the foundation for the current financial crisis.

Steward Executive Were Major Donors to Coakley, Healey

But even more concerning is the appearance that not only did Cerberus and Torre benefit from the Attorney General’s Office’s decision, but also that the Coakley and her associates, including her mentee Maura Healey, benefitted from the support of Torre and co. Public records available on the Office of Campaign and Political Finance website reveal a number of donations which raise serious questions.

Following the August 2009 death of Senator Ted Kennedy, Attorney General Coakley declared her candidacy for the open senate seat in September. On October 28, 2009, Ralph de la Torre donated $5,000 to the Democratic State Committee, MA, money which helped fund the Democratic Party’s support for Coakley against Republican candidate Scott Brown. Torre received his first favorable ruling the following year.

Ralph continued his financial contributions to Democrats. He contributed maximum donations to both Coakley and her primary rival Warren Tolman in their 2014 bids for governor. Just months after the AG office, in January of 2015, declined to enforce its 2011 no-close agreement at Quincy Medical Center, Torre contributed a maxxed-out donation to the new AG, Maura Healey, presumably to help her pay off campaign debt. He continued to make maximum contributions to Healey in her 2018 re-election bid and her 2022 bid for governor.

Some of these donations were matched on the same day by donations from his wife, and possibly also other de la Torre family members from out of state. These donations from Ralph were also echoed, often on the same day, by maxed-out contributions to Coakley and then Healey by other higher-ups at Steward Health, including by the hospital chain’s president, vice-presidents, board members, multiple of its attorneys, and members of its executive team.

According to data available at FollowTheMoney.org, 14 donations from only 10 employees of Steward Health, all of whom are in leadership, were collectively the 10th largest donor group by employer to Healey’s 2018 re-election campaign. And combining all her campaigns, Steward Health executives have been the 20th biggest supporters of Healey when grouping donations by employer.

Coakley’s approval of the Cerberus buyout of Caritas Christie and later empowerment of Steward’s expansion, and Steward’s significant contributions to Coakley and Healey are hardly new or unique. Rather, they are part of a larger embrace by Democrats of neoliberal policies to privatize public goods and generally to profit off of public office. Indeed, after leaving office Coakley served as a government affairs officer for Juul Labs from 2019 to 2022. Democratic governor Deval Patrick, who served from 2007 to 2015 during the time of Steward’s rise, took a position at Bain Capital. But considering the timing of substantial donations which often occurred closely before or after favorable regulatory rulings by the AGO, and when considering that the initial ruling which empowered Cerberus’s buyout was unprecedented at the time, they certainly present the optics of quid-pro-quo and raise questions.

To be clear, evidence of substantial contributions from Steward Health executives is not proof of a quid-pro-quo relationship or legal malfeasance. But any resident would be right to conclude that the difference between explicit quid-pro-quo and a wink and nod agreement is a mere technicality; either way, both Steward Executives and politicians at the AGO profited from the mutually beneficial relationship.

Perhaps the friendly history of the AGO with Steward executives explains why Healey has taken such a strong and public stance against Steward in the current crisis, in order to head off potential criticism. But Governor Healey cannot hide her history with Steward by blustering political statements. Instead, she must answer questions about her role in the making of this tragic – but entirely predictable and preventable – crisis in the Commonwealth.

Henry De Groot is an editor of Working Mass.

“}]]