[[{“value”:”

Remembering the 8-week Strike on its 113th Anniversary

By Ben Cabral

LAWRENCE – On January 11, 1912, women textile workers walked off their jobs in protest of a cut to their pay. The industrial action would quickly grow to include more than 20,000 textile workers, and last for 8 weeks, becoming one of the most important labor struggles in Massachusetts and US labor history, and earning the name “The Bread and Roses Strike.” But what made this strike so important?

In part, the importance of the strike was because it was waged by workers – ‘unskilled’ or semi-skilled, women, immigrants – who had largely been written off as ‘unorganizable’ by the conservative union establishment of the American Federation of Labor. But in spite of being written off by the establishment labor movement, primarily immigrant women from at least 51 different nations were able to band together, overcoming significant language and cultural barriers, to challenge the power of capital and win their primary demands addressing low wages, and unsafe working conditions.

The Bread and Roses Strike also was marked for the role played by some of the titans of the labor movement in the early 20th century, including Industrial Workers of the World leaders Big Bill Haywood and Elizabeth Gurly Flynn.

The strike saw the implementation of many new tactics and substantial victories that created a blueprint for subsequent strikes which helped to expand the labor movement beyond the relatively privileged layers of native-born, high skilled workers organized by craft, and into the far larger layers of semi-skilled industrial workforce of the mass-production industries. Although it would not be for another two decades that the Congress of Industrial Organizations (CIO) split from the AFL in order to fully embrace this industrial model of mass-organizing, this later split would not have been possible without the earlier efforts at industrial organizing which were, in part, kicked off by the Bread and Roses Strike. The historical impact of this strike means it is important for the modern labor movement to study its development and be able to implement the lessons of this strike, to win the rights that the working class deserves.

Slaves To The Loom

The city of Lawrence, Massachusetts was founded in the 1840s explicitly as a one-industry town to expand the textile industry out of Lowell, another nearby textile hub. By 1912, Lawrence was the textile capital of the United States, with a workforce made up primarily of Southern and Eastern Europeans, specifically Poles, Italians, and Lithuanians, as well as some Russians, Portuguese, and Armenians. There were also some smaller immigrant communities in Lawrence, most notably Syrians. The majority of the city’s black population also worked in the textile mills, although they made up a small percentage of the overall workforce. Many of these immigrant workers were women and children, who were intentionally hired after the mechanization and deskilling of textile mill labor, who could be paid significantly less.

The working conditions in the mills were appalling. Poet William Blake summed it up perfectly as “these dark satanic mills.” Workers were regularly forced to work 6 days a week for 60 or more hours.1 Workers were frequently killed, maimed, or seriously disabled due to workplace accidents, while others died slowly from inhaling toxic fibers and dust. The life expectancy of a textile worker at this time was about 20 years lower than the rest of the population. In fact, over a third of workers in the Lawrence mills died before the age of 25, and 50% of children born to workers died before the age of 6.2

Early Organizing

Even before the strike broke out, and in response to the terrible conditions outlined above, there was a high degree of organization among the textile workers. There was an AFL union, the United Textile Worker, which claimed to represent several thousand of the more skilled textile worker, but in reality this union only counted a few hundred dues-paying members, evidence of its weakness even among the “organizable” minority of skilled worker, more likely to be native born men. Far more energetic was the organizing of the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW), which had been active in Lawrence for 5 years prior to the strike. The IWW in Lawrence had 20 different foreign language chapters operating in the city to accommodate the various immigrant communities in Lawrence at the time. The Italian Socialist Federation (ISF), part of the Socialist Party of America, was also active in Lawrence at the time, and had some overlap with the IWW. In addition, many of the immigrant workers had experiences in cooperatives and unions in Europe and were able to use those experiences once they got to the United States.

In fact, the workers had already been organizing, forming “shop committees” in the various textile mills to democratically relay their demands to the textile bosses, with organizing assistance from the IWW. In the fall of 1911, mill owners had refused to meet with the shop committees to discuss the upcoming cuts to working hours. The workers wanted assurances that their pay wouldn’t be reduced, since wages were already incredibly low. The mill owners’ refusal to meet with the shop committees agitated workers, who had also been struggling against long hours, horrible working and living conditions, and high infant mortality rates, along with the poor pay.

Although the Bread and Roses Strike is often painted as a spontaneous action, it was actually these years of organizing, at least half a decade prior to the strike, which enabled workers to take the flashpoint of reduced wages and turn that into a massive 8 week strike.

The Strike Breaks Out

On January 11, 1912, a number of Polish women working at the Everett Mill in Lawrence, Massachusetts opened their checks and discovered that their pay had indeed been cut by 32 cents due to the slightly reduced work hours.

32 cents may not sound like a significant reduction in pay, however, wages had already been so low, about $8.76 a week, that this reduction was substantial. This group of Polish women proceeded to shut off their machines and started marching around Lawrence, taking to the other mills to notify the other workers of their strike over the cuts in pay, and later that night, word of what happened at Everett Mill spread around the workers’ tenements. The women of the Everett Mills’ brave actions clearly struck a nerve, as the next day, on January 12, some 10,000 workers shut off their machines and went on strike across the city. On the first day of the strike, workers slashed the belts on their machines and threw bricks through factory windows to protest their low pay and horrible working conditions and their bosses’ refusal to listen to them. And as news of the strike spread, farmers wanting to support the workers drove to Lawrence in order to donate whatever they could for food.3

Joseph Ettor of the IWW and Arturo Giovannitti of the ISF took the lead and formed a 56 person strike committee with 4 representatives from 14 different nationalities. This created a strong worker-led democratic leadership team with strong roots among the various sections of the workforce. This model was uncommon if not unique at the time, and stood in direct contrast to the typical AFL craft union model where the union bureaucracy had final say on everything. This robust democracy, which ensured representation for all the ethnic groups in the city, created a deep sense of belonging and unity for the workers which proved crucial when the United Textile Workers (UTW) tried to break the strike, claiming that they were the union that spoke for the workers. Because the workers felt such a strong sense of ownership in their movement, seeing the IWW as their vehicle for collective power, they stood behind the IWW leadership and ignored the UTW.

Another important aspect in building community among the workers was the effort made to cultivate deep connections between workers outside of working hours. The women in the city deliberately formed networks in the different ethnic neighborhoods of Lawrence. The language and cultural barriers were overcome through community spaces like soup kitchens, ethnic organizations, and community centers. These spaces brought the various immigrant communities in the city together, creating a sense of connection and commitment to each other.

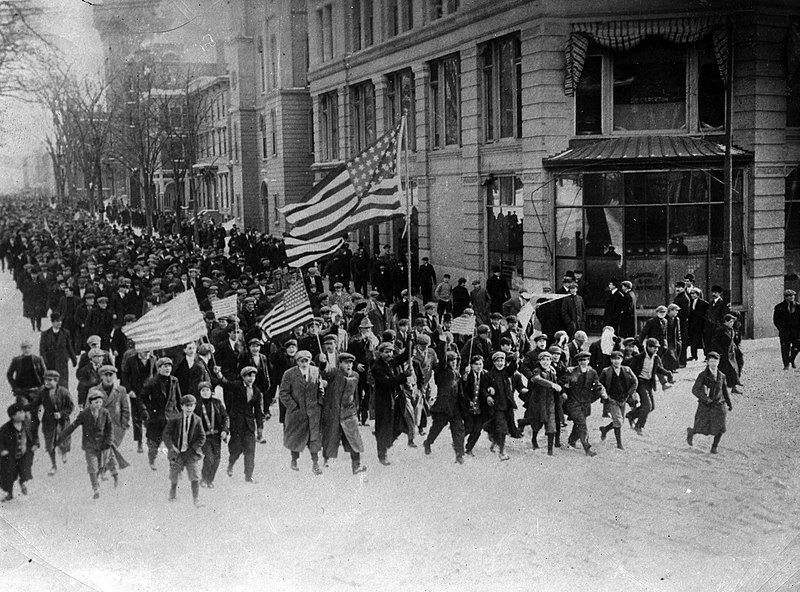

During the strike, the workers did more than hurting company profits by keeping factories closed and destroying mill property. In addition, they also actively worked to build mass support. They organized massive marches through the city with singing, chanting, and banners. The call for higher wages (Bread) and workplace dignity (Roses) was a consistent theme, and led to the chant from which this strike gets its name “We want bread and roses too.” Workers also entered stores in large numbers around the city to halt operations and create further disruptions. A key aspect to this strategy was to keep the pressure on the mill owners through these large public displays and keeping the mills closed, while also avoiding any unnecessary provocation or property destruction. The strike leaders were very aware of the need for public support and were deliberate in maintaining a positive image in the public as much as they reasonably could.

These tactics would prove to be crucial in making sure material support was available to the strikers to help them maintain the strike and withstand the retaliation from the capitalist class.

Mill Owner Retaliation

The mill owners, the City of Lawrence, and the Commonwealth of Massachusetts reacted to the strike with mass violence, revealing to the workers of Lawrence that the government was not a neutral party, but rather clearly in the pocket of the capitalist class. Police and state militiamen were called in to beat back the striking workers and protect the mills. Police used clubs to beat workers as they marched through the streets and picketed at their mills, while state militiamen stood around the mills with their bayonets pointed at the picketing workers. The police even killed two strikers, Anna LoPizzo and John Ramey, during a struggle between striking workers and scab workers that were being brought into the mills. The authorities later charged Ettor and Giovannitti as accomplices to the murder of Anna LoPizzo, even though they were nowhere near the scene when her murder actually took place. This was clearly an attempt by the state to disrupt the strike by targeting two of its leaders.

Later when striking workers began to send their children to other cities, such as New York, Philadelphia, etc, police were present at the train stations and proceeded to beat and arrest the mothers there who were trying to send their kids to safety. Those same kids were forced to watch this ordeal, no doubt traumatizing them.

But the mill owners did not stop with leaning on state repression, they also resorted to framing and discrediting the strikers. Mill owners hired a group of agitators to foment trouble among the strikers and even had a group plant dynamite near one of the mills in order to discredit the strikers. The man who was found to have planted the dynamite was not imprisoned, and was given a small $500 fine. It was later revealed that William M. Wood, president of the American Woolen Company which owned a number of the mills in Lawrence, had made a large payment to the man just before he had planted the dynamite.

The history of repression brought in by the state on behalf of the mill owners is a great reminder of who the state serves and the lengths they will go in order to protect capital. But the workers’ resistance, including their continuation of militant tactics paired with their savy appeals to public support, shows that even the unity of the capitalists and the state is no match for the unity of the militant working class.

The Strike Comes To An End

The stories of police brutally beating the mothers of Larence created outrage around the country. So much so that President Taft ordered the attorney general to investigate the strike and Congress began a hearing on March 2nd, 1912. Testimony from workers about the horrible working conditions and abject poverty dramatically shifted public opinion of the strike in favor of the workers. They highlighted diseases contracted by workers from inhaling dust and debris, deaths to workers due to workplace accidents, and others appalling stories. Specifically, a 14 year old girl named Carmela Toreli told the story of how her scalp was ripped off by one of the mill machines, which left her hospitalized for seven months.

The massive shift in public support for the strikers, and the public pressure placed on the mill owners as a result, forced the mill owners to come to the table and discuss the demands of the workers. And by March 14th, workers and mill owners had reached an agreement that included a 15% wage increase for workers, an increase in overtime compensation, and a guarantee not to retaliate against the striking workers. This victory led to similar wage increases for 275,000 New England textile workers and workers in other industries as well. This result revealed the power of the industrial union model promoted by the IWW, and later by the Congress of Industrial Organizations (CIO), as opposed to the craft union model promoted by the AFL. Rather than trying to organize unions based on a specific job, the IWW focused on organizing unions based on industry as a means to unite all the workers in a given industry and allow them to have significantly more bargaining power and for the benefits of their wins to apply to more workers.

Meanwhile, Giovannitti and Ettor remained in jail for months after the end of the strike. Bill Haywood and the IWW threatened a general strike if they were not released. On March 10th, 1921, a 10,000 Lawrence workers protested for the release of Ettor and Giovannitti, and then later, on September 30th, 15,000 Lawrence workers went on strike to demand their release.4 There was even an international campaign for their release, with Swedish and French workers proposing a boycott of woolen goods from the US and protests in front of the US consulate in Rome. Fortunately, Ettor and Giovannitti, and a third defendant, who had never even heard of either of them and was at home eating dinner at the time of the killing, were all acquitted on November 26th 1912.

As many of the textile mills began to move south, efforts were made specifically by the Communist Party of the United States of America (CPUSA) to organize southern textile mills. CPUSA had begun organizing their own unions separate from the AFL, based foremost on their experience trying to bore within the AFL, but also in part being influenced by the Communist International’s (Comintern) position that world revolution was approaching due to the crisis of Capitalism and that communists should organize their own organizations, including unions. Southern mill towns were much more tightly monitored due to the mill owners’ tiger connections with local police, which made organizing much more difficult there. However, the CPUSA did have some early success organizing workers in the National Textile Workers Union (NTWU) which they organized through the Trade Union Unity League (TUUL), including the famous strike at the Gastonia Mill in North Carolina. Ultimately, some of the high profile strikes by AFL unions and the rise of the CIO made many organizers within TUUL decide to rejoin the mainstream labor movement, which ultimately led to a dramatic reduction in the organizing efforts of these southern textile mills.5

Lessons of the Strike

The Bread & Roses Strike is a reminder of the power of workers when they are organized and militant. Immigrant women are one of the most vulnerable groups in the United States, and yet this group of immigrant women were able to use their collective power as workers to deliver one of the most substantial wins in American labor history. One of the most important factors of the strike was the community built by the women in Lawrence through workplace organizing. This was crucial to overcoming the vast cultural differences among the workers and cultivating the sense of obligation to each other and the solidarity necessary to withstand the state repression, and build the networks of support for the strikers that allowed them to maintain the strike for 2 months. The strike committee was also crucial in maintaining unity among the workers, specifically the move to ensure representation for each of the ethnicities present among the workers was in place. This is similar to the practice of “mapping the workplace” in order to find natural leaders among the workers, which is so important in any successful unionization campaign.

Many leaders of the IWW ended up leaving the IWW in favor of boring from within the reactionary AFL union. This came as a result of the failures of the IWW mentioned above in the previous section. This was more in line with the general marxist-leninist position of how to interact with trade unions, which Lenin had described in “Left-Wing Communism: An Infantile Disorder”. The basis for this position is that communists need to be doing their work within the unions that the mass of workers most commonly reside in, even if those unions are led by more conciliatory labor partners of the capitalist class.

Remembering our power as workers and making sure that we are talking with and making connections with our co-workers and with our communities will be crucial for the labor movement. Winning more substantial victories will require the courage of rank and file workers, and also the solidarity of other workers to build support systems for striking workers and isolate the employers by refusing to cross the picket line. And this can only be built through deliberate community building and organizing like what was done in the lead up to the Bread & Roses Strike.

Ben Cabral is a member of Boston DSA and contributor to Working Mass.

Photo Credits:

“Bread and Roses Strike of 1912: Two Months in Lawrence, Massachusetts, that Changed Labor History” Digital Public Library of America online exhibition

https://dp.la/item/3420c6a58eb17c992594e2e0f110980e

Remembering the 1912 Lawrence Textile Strike – AFRICANIST PRESS ︎The Lawrence Textile Strike https://reuther.wayne.edu/node/8239 ︎The Strike That Shook America ︎Crossing Borders on the Picket Line: Italian-American Workers and the 1912 Strike in Lawrence, Massachusetts on JSTOR ︎Trust the Bridge That Carried Us Over: The Failure of Operation Dixie 1946-53 – Cosmonaut ︎“}]]