[[{“value”:”

By Richard S

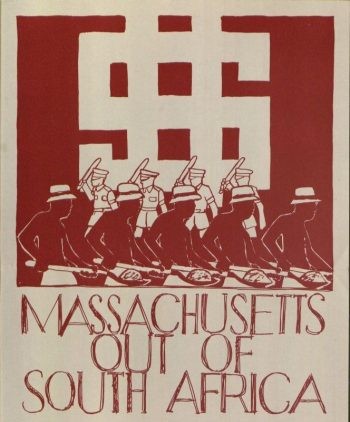

Cambridge, MA – Massachusetts labor activists were some of the first movers to confront South African apartheid and push for US divestment and sanctions. These efforts bore fruit in 1982 legislation divesting Massachusetts pension funds, Boston municipal divestment in 1984, and federal sanctions in 1986. Throughout the late 20th century, labor activists in Boston kept the issue of apartheid firmly on the agenda until the African National Congress (ANC) leadership supplanted apartheid and established a progressive constitutional democracy.

Today, American workers confront another criminal regime. In July 2024, the International Court of Justice (ICJ) found Israel to be practicing “racial segregation and apartheid” in occupied Palestine. In Gaza, Israeli forces have resumed what Human Rights Watch and international institutions around the world call genocide, “acts committed with intent to destroy, in whole or in part, a national, ethnical, racial or religious group.” According to a recent YouGov poll, only 15% of Americans support increasing military aid to Israel. Public favorability toward Israel has cratered across all partisan and age demographics over the past three years. Given this bedrock of anti-apartheid sentiment, we can look to the New England struggle against South African apartheid as inspiration to end its Israeli form.

Workplace Roots of Anti-Apartheid Struggle

In 1970, at the Polaroid Corporation in Cambridge, MA, two Black employees – chemist Caroline Hunter and photographer Ken Williams – discovered the South African government was using Polaroid’s cameras to produce passbook photos – the internal passports enforcing racial segregation. Outraged that their labor aided oppression abroad, Hunter and Williams formed the Polaroid Revolutionary Workers Movement (PRWM) and launched the first anti-apartheid boycott of a U.S. corporation. They demanded Polaroid withdraw from South Africa through a pressure campaign that included rallies at Polaroid’s Cambridge headquarters. Pressure worked. By 1977, Polaroid ended all business in South Africa after a failed attempt at “responsible engagement” collapsed under public scrutiny.

In the wake of the 1976 Soweto Uprising, Boston activists formed the Boston Coalition for the Liberation of Southern Africa (BCLSA) alliance fighting white minority rule. Labor organizers coordinated boycotts and educational events. Black American trade unionists in particular took the lead: in 1975, the national Coalition of Black Trade Unionists (CBTU) broke with the conservative AFL-CIO and passed a resolution supporting the exiled South African trade union federation aligned with Nelson Mandela’s ANC. CBTU became the first U.S. labor body to call to boycott apartheid.

New England Labor at the Leading Edge

As South Africa’s repression intensified, New England labor activists championed divestment – pulling financial investments out of companies tied to South Africa. In 1979, State Representative Mel King of Boston and State Senator Jack Backman introduced legislation to divest the state’s public-employee pension fund from banks and corporations doing business in South Africa. At first, their bill lacked enough support. Understanding that broader grassroots backing was needed to overcome political inertia and corporate lobbying, they helped convene a meeting of unions, church groups, and anti-apartheid activists across Massachusetts.

Unionists testified that worker pension dollars should not fund apartheid. They linked factory shutdowns in Massachusetts to companies seeking cheap, non-union labor in South Africa.

These forces merged to form the Massachusetts Coalition for Divestment from South Africa, or Mass Divest. Crucially, labor unions were at the coalition’s heart, including locals of the Service Employees International Union (SEIU), American Federation of State, County and Municipal Employees (AFSCME), and Massachusetts Teachers Association. By uniting labor with religious and student groups, Mass Divest built a broad constituency in favor of cutting Massachusetts’ economic ties to apartheid. As Mass Divest rallied public support through petitions, pamphlets, and public hearings, the campaign gained momentum. Unionists testified that worker pension dollars should not fund apartheid. They linked factory shutdowns in Massachusetts to companies seeking cheap, non-union labor in South Africa.

In 1982, their efforts paid off, as the Massachusetts legislature passed a sweeping pension divestment bill requiring the state to sell off all investments (around $100 million) in companies doing business in South Africa. Conservative governor Edward King vetoed the bill. In a dramatic show of unity, lawmakers overrode his veto – the only override of King’s tenure. The new law, enacted in 1982, made Massachusetts the first U.S. state (alongside Connecticut that same month) to divest its public pension funds from South Africa. Massachusetts’ divestment law – described at the time as the toughest in the nation – passed through a concentrated campaign led by a bedrock of labor unions and activists in Massachusetts. Union activists provided much of the grassroots muscle behind Mass Divest, lobbying legislators and educating rank-and-file workers on why apartheid investments were immoral. The state AFL-CIO and major unions formally endorsed the campaigns in resolutions and lobbying officials.

Inspired by the state’s stance, Boston City Councilor Charles Yancey successfully introduced a Boston city ordinance in 1984 requiring Boston to withdraw its funds from companies tied to apartheid – a measure similar to a proposal by Somerville for Palestine to Somerville City Council in March 2025. “Today’s divestment legislation is one more hammer blow against the chains of apartheid,” declared Yancey in 1984. This made Boston the first major American city to divest municipally, selling $12 million in stocks and leading to policy transfer across the country as cities and states took Boston’s law and codified it into their own books. By 1986, the U.S. Congress, prodded by a broad coalition prominently featuring labor, overrode President Reagan’s veto to enact the federal Comprehensive Anti-Apartheid Act, imposing economic sanctions on Pretoria.

Labor Building Base, Boycotts, and Networks of Solidarity

New England labor did not just lobby for legislation; their memberships took more direct action to isolate the apartheid regime. Trade unions passed strong anti-apartheid resolutions throughout the 1980s, committing union resources and moral authority to the cause. For example, Massachusetts AFL-CIO under President Arthur Osborn vocally supported sanctions. So did local labor councils; the Greater Boston Labor Council regularly urged its affiliates to boycott firms complicit in apartheid. National unions such as the United Auto Workers (UAW) and American Federation of Teachers (AFT) denounced apartheid’s exploitation of workers. West Coast longshoremen in 1984 boycotted South African cargo ships, inspiring unionized dockworkers and truckers in the Northeast.

Unionized city workers even removed Shell products from municipal garages.

Unions also joined campaigns targeting specific corporations. A notable one was Shell Oil, part of an international boycott to pressure Royal Dutch/Shell to withdraw from South Africa. Boston became a key front in this campaign. In December 1988, Boston’s mayor Raymond Flynn (former labor organizer) issued an order flanked by labor leaders declaring the city government “Shell Free” – no city agency would buy Shell gasoline until the company cut ties with apartheid. Boston’s unions enthusiastically backed Flynn’s order; unionized city workers even removed Shell products from municipal garages.

Finally, Massachusetts activists built relational networks of solidarity with South African liberation movement organizers. Union locals hosted South African trade unionists and anti-apartheid leaders on speaking tours. Labor-affiliated groups raised funds for Black union organizers in South Africa who were jailed or fired by apartheid authorities. For instance, Boston-area unionists sponsored the defense of imprisoned labor leaders such as Oscar Mpetha and funneled material aid to newly independent Black unions in South Africa like the National Union of Mineworkers. In June 1983, Northeast activists formed a Labor Committee Against Apartheid to coordinate letter-writing drives.

When Nelson Mandela was liberated from prison in 1990, he made a point to visit Boston. Speaking to a jubilant crowd of 300,000 on the Charles River Esplanade, Mandela praised “the pioneering and leading role of Massachusetts.” The long-incarcerated leader of the South African freedom struggle cited the early Polaroid protests of 1969–70 as proof that Bostonians “rallied around our cause when we soldiered on by ourselves…You became the conscience of American society.”

Mandela’s praise was not just empty rhetoric. As recounted by scholars like Kathleen Schwartzman, Kristie A. Taylor, and Stephen Zunes, international sanctions and other restrictions on South African capital played a decisive role in apartheid’s collapse.

Today: Labor and the Struggle for Palestine

Labor’s fight against apartheid in South Africa shows us divestment and sanctions can be effective tools to isolate racist regimes. It continues today in the BDS (Boycott, Divestment, Sanctions) movement against Israel. Just as our unions once opposed apartheid South Africa, unions today, such as the UAW, UE, tenant and teachers’ unions are taking up the baton of solidarity with the Palestinian people. Crucial to the earlier generation’s success was building a broad, popular coalition across religious, labor, and student groups in coordination with allied lawmakers.

For our predecessors, “an injury to one is an injury to all” was not just a moralizing cliché. It was an analytic necessity that grounded the struggle for universal justice in shared class interest, the same class interest that leads workers to oppose Trump’s mass firings, the plunder of the commons, attacks on free speech, science, public health, and social insurance. As the war on Gaza deepens in its cruelty, and as the occupation of the West Bank and Gaza nears its fifty-eighth year, the fight for an arms embargo and broader sanctions will be fought by labor.

Richard S is a member of UE Local 256 and Boston DSA. He is also a doctoral student in political science at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

“}]]