By Henry De Groot

The views expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not represent the official position of Working Mass.

DSA Emerges as a Force in Labor

As the Democratic Socialists of America has grown into the country’s largest socialist organization in recent memory, its work in the labor movement has taken tremendous steps forward.

Thousands of union members, staffers, and other labor activists have joined our ranks as individuals, and many comrades have taken jobs in strategic industries. Our labor branches (also called working groups, committees, etc) around the country have engaged at all levels of labor struggle, from new organizing drives to strikes and strike solidarity to reform caucuses and internal elections.

This growth represents DSA’s arrival as a real force in the labor movement. As AFA-CWA president Sara Nelson told Working Mass when interviewed on the 874 Comm Ave Starbucks picket line, “DSA is everywhere — every single picket line that I go to — every single fight, they’re taking up the cause, talking about labor rights, making it central to the mission.”

But what role should DSA play in the labor movement? And what lessons can we draw from history to sharpen our strategy and multiply our impact?

While no organizational model should be directly reproduced, in my opinion, the Trade Union Educational League (TUEL) provides one of the best frameworks for guiding our socialist labor efforts today.

The Founding of the TUEL

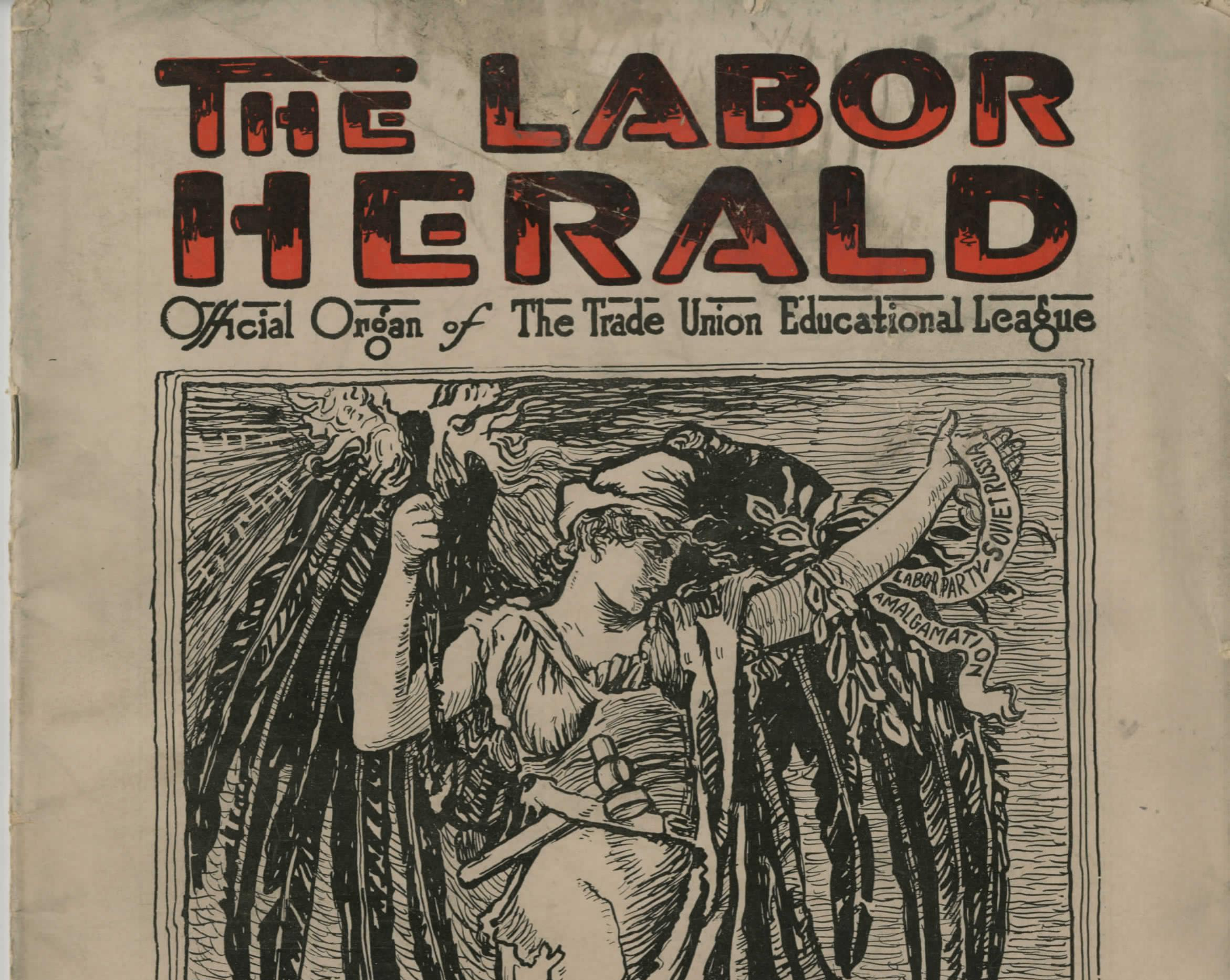

Technically, the TUEL was founded in 1920, but TUEL activists themselves date its founding to 1922, the year that it launched its publication The Labor Herald and began its work in earnest, which was 100 years ago this year.

The TUEL was launched by former IWW organizer William Z. Foster and a handful of radical labor activists in November 1920. But soon after its founding, Foster headed to Soviet Russia to attend the founding of the Red International of Labor Unions (RILU). Impressed by the proceedings, he joined the Communist Party on his return and worked to gain its endorsement of the TUEL.

Armed with the well-developed labor strategy of the Bolsheviks and the political backing of the growing Communist Party, Foster began planning for The Labor Herald, and to transform the TUEL from “little more than a few scattered groups throughout the country” into the beginnings of a well-organized movement. In February 1922, directions for forming local TUEL sections were circulated, and the first issue of The Labor Herald was launched in March.

The front and back cover of the first issue of The Labor Herald.

The major orientation of the TUEL was the rejection of the IWW’s independent unionism in favor of embracing campaigns “boring from within” the established AFL unions to promote militancy and radicalism. In an attempt to protect TUEL activists from expulsion for dual unionism, the act of setting up separate and competing unions, the TUEL organized not as a union but as an educational body. It prohibited national and local unions from affiliating and maintained no true membership dues but rather only subscriptions to The Labor Herald and donations (See: TUEL Constitution). The TUEL organized by location and section, developing both local educational groups and correspondence within industries, and was open to all radicals, not only Communist Party members.

The TUEL held its founding conference in August 1922. Delegates were proportioned to the local TUEL bodies by their number of local subscribers, with members active in the locals entitled to vote. Delegates from 14 recognized industries each elected a secretary to oversee the development of the TUEL’s work in their industry. Together with one secretary-treasurer elected by the entire conference, these 15 individuals formed the national leadership of the TUEL.

Amalgamation and Industrial Unionism

While the TUEL aimed to educate militants, it always tied its work to concrete campaigns for the re-direction of the labor movement toward militancy. Beginning in 1922, the TUEL embarked on a well-organized program for amalgamation and industrial unionism. Amalgamation and industrial unionism are two parts of the same process. Amalgamation involves the uniting of existing unions within the same industry. Industrial unionism is an overall logic of how trade unions should be organized to maximize worker power — by industry instead of craft — which includes amalgamation but also the reassignment of some workers between existing unions.

In the 1920s, the American Federation of Labor (AFL) and the wider labor movement consisted of a strange mix of unions, many of which organized similar workforces in the same industry. The TUEL called for amalgamation, and the second issue of The Labor Herald launched the TUEL’s campaign for amalgamation of the 16 existing railroad unions into one national railroad union.

The TUEL organized its campaign by winning rank-and-file support for its strategy. A proposal for amalgamation went out to 12,000 railroad locals, with 4,000 locals endorsing the proposal. The TUEL and its activists in the railway unions then called a national conference of railway workers to facilitate the effort, which was held in December 1922 with 425 delegates from across the United States and Canada (See: “Amalgamation Movement in America” Feb 6, 1923).

The railroad campaign for amalgamation was the spearhead for a wider push to promote the general strategy of industrialization of the unions. The same tactic of passing resolutions was used, and the first resolution calling for the AFL to embrace the industrial model over the craft model of organizing was adopted by the Chicago Federation of Labor. By February 1923, the Minnesota, Colorado, Utah, Washington, Oregon, Nebraska, South Dakota, Michigan, Ohio, Indiana, and Wisconsin state federations, the Railway Clerks, Railway Trackmen, Butchers, Firefighters, Typographical, Men’s Clothing Workers, and Food Workers national unions, and several thousand local unions and central trade councils had all adopted proposals for the restructuring of the unions along industrial lines.

Conservative trade union officials, long protected by the craft union model, were alarmed by the campaigns for amalgamation and industrial unionism. Many officials opposed the efforts; some succeeded in organizing resistance, while others were swept out of office by supporters of the TUEL’s industrial vision.

While many unions did undergo amalgamation, a serious step toward industrial unionism, the larger campaign for industrial unionism failed to move the AFL away from the craft union model. However, a foundation was laid for the birth of the Congress of Industrial Organizations, which broke from the AFL in the 1930s and took up the banner of industrial unionism.

Overall, these campaigns showed the impressive organization of the TUEL and that it already had the ability to engage massive swathes of the labor movement by the end of 1922. By bringing proposals to strengthen the labor movement to the rank and file and overseeing these campaigns with a centralized national leadership team and militants organizing in concert throughout the country, the TUEL was able to engage workers far beyond the typical reach of the Communist Party.

Building Support for a Labor Party

The TUEL also engaged union members to promote a break between the labor movement and the Democratic and Republican parties. Earlier radicals in the IWW had rightly condemned Democrat and Republican politicians as servants of the bosses, but Foster and his co-thinkers made clear that the IWW had gone too far by swearing off electoral politics entirely.

A document published in the December 1922 issue of The Labor Herald outlined the TUEL’s position on the need for an independent workers’ movement. In the article, the TUEL’s national leadership calls for the formation of a united front labor party, founded on the basis of the interests of the working class and embracing all existing working-class parties. Within this party, they proposed, political formations would be able to retain their own identity while participating in common action.

While the document calls for the inclusion of the exploited small farmers, it makes clear that the labor movement must be the dominant force in the party and that to be successful the unions must affiliate. The TUEL’s leadership also envisioned a party that included both a “maximalist” (revolutionary) call for a workers’ government with “minimalist” (reformist) demands around immediate issues such as regulations on wages and working conditions.

As with amalgamation, the TUEL located the main obstacle for the establishment of a labor party in the corruption and conservatism of the union officialdom, making it clear that such a party would be built only by organizing masses of union members in struggle with their union leaders.

The Bolshevik Ideology of the TUEL

While the TUEL was undoubtedly anchored in the concrete issues of the labor movement, some historians have attempted to distort it by focusing only on the practical concerns of amalgamation, industrial unionism, and the building of a labor party.

Although the TUEL was not focused on spreading abstract socialist ideas, it did embrace a larger political ideology hardly in line with a model of simple mobilization of workers on everyday issues. The TUEL leadership put forward Lenin’s model of class struggle in simple terms, and educated workers on the history and current developments of the international Communist movement and especially events in Soviet Russia.

The essence of this Bolshevik model, the key role of the militant minority, was spelled out in one of the TUEL’s founding documents, The Principles and Program of the Trade Union Educational League, published as the first article in the first issue of The Labor Herald.

One of the latest and greatest achievements of working class thinking, due chiefly to the experiences in Russia, is a clear understanding of the fundamental proposition that the fate of all labor organization in every country depends primarily upon the activities of a minute minority of clear-sighted, enthusiastic militants scattered throughout the great organized masses of sluggish workers. These live spirits are the natural head of the working class, the driving force of the labor movement. They are the only ones who really understand what the labor struggle means and who have practical plans for its prosecution. Touched by the divine fire of proletarian revolt, they are the ones who furnish inspiration and guidance to the groping masses. They do the bulk of the thinking, working, and fighting of the labor struggle. They run the dangers of death and the capitalist jails. Not only are they the burden bearers of the labor movement, but also its brains and heart and soul. In every country where these vital militants function effectively among the organized masses the labor movement flourishes and prospers. But wherever, for any reason, the militants fail to so function, just as inevitably the whole labor organization withers and stagnates. The activities of the militants are the “key” to the labor movement, the source of all its real life and progress.

It needs to be stated that by militant minority, the TUEL leadership meant especially, albeit not exclusively, the communists within the labor movement.

In general, The Labor Herald did not try to convert its readers to Marxism by direct appeal. However, it did educate them on Marxist theory in language that would be readily received by practical workers. For example, the article “Wages, What Are They?” outlined the Marxist conception of wages in plain English and concluded with the vision of a society free from wage labor (Vol 1 No 6, Aug 1922). It also drew lessons from socialist labor history, as in the article “The Workers Internationals” (Vol 2 No 7, Sep 1923), and provided coverage of international labor developments, drawing clear socialist positions without using theoretical jargon.

Frequently, The Labor Herald held up the Bolshevik party, the October Revolution, and the Soviet government as a model for radicals in the U.S. labor movement. Of note are the TUEL’s publications of Foster’s pamphlet The Russian Revolution, Losovsky’s Lenin and the Trade Union Movement, and the section of the TUEL’s principles quoted above. Articles like “Discipline vs Freedom in Russia,” published in the very first issue of The Labor Herald, and “Fascisti and Bolsheviki” (Vol 1 No 11, Jan 1923) defended the tough methods of the dictatorship of the proletariat in no uncertain terms. And The Labor Herald called unequivocally for affiliation to the Communist-led RILU (“Which International” Vol 1 No 2, Apr 1922) and published reports on its congresses (“After the Second Congress” Vol 1 No 12, Feb 1923).

The ideology of the TUEL was three-tiered. On a broad scale, it defended revolutionary socialism in general, while framing its expositions in concrete terms and examples and avoiding abstract theory. On the level of concrete action, it called for the unions to take up militant strategy and tactics, such as amalgamation. But perhaps most importantly, and tying these first two factors together, it raised the keystone role of the conscious minority, calling for militants and radicals in the labor movement to unite within a centralized organization to facilitate their work among the broader union membership; as the TUEL explained without apology, this third factor was Lenin’s vanguard model as applied to the labor movement.

In “The Rank and File Strategy,” which has popularized the legacy of the TUEL among a new generation of socialist labor activists, Kim Moody writes that the TUEL “stood, above all, for industrial unionism and a labor party.” Moody briefly acknowledges the internal organizing of the TUEL before focusing almost exclusively on exploring its external campaigns.

Of course, the TUEL did stand for industrial unionism and a labor party. But as quoted above, for Foster “the activities of the militants are the ‘key’ to the labor movement, the source of all its real life and progress.” Moody entirely passes over the TUEL’s focus on organizing the organizers, which at least for the TUEL’s leadership was the most fundamental issue.

In my opinion, it may be useful to consider Foster’s thesis as a sort of ‘hyper-consciousness’ or ‘meta-consciousness.’ It is not enough for us to be aware of the role of workers and their unions in the fight for socialism, that is, to have socialist consciousness. Rather, we must also be aware of what role must be played by those who have achieved socialist consciousness, and how they may best organize to infuse socialist consciousness through the class struggle, that is, a consciousness of the development of socialist consciousness.

The Demise of the TUEL

A history of the TUEL would not be complete without at least a brief note on its demise. As they succeeded in building mass resistance, TUEL and Communist Party members faced increasing resistance from and eventually widespread expulsions by the AFL unions as early as 1924.

Kim Moody also faults the Communist Party’s influence — or in his words “domination” — of the TUEL for its decline.

The greatest weakness of the TUEL was that it was controlled top-down by the CP. It never really developed a democratic structure of its own, nor an independent rank and file leadership to combat the growing sectarianism and erratic behavior of the CP. The TUEL’s lack of independence was signaled among other things by its affiliation with the Moscow-controlled Red International of Labor Unions. More importantly, virtually all the leaders of the various TUEL bodies were CP members. Both of these realities left TUEL without a self-organized base and unnecessarily open to red baiting.

But this criticism misses the mark. The issue was not that the Communist Party played a leading role in building the TUEL — quite the opposite, as it was the energetic work of the Communists that rapidly built the TUEL into a fighting force. The real issue was the shift in policy of the Communist leadership that resulted from Stalin’s consolidation of power and his misguided embrace of dual unionism in 1928. Following this line, the TUEL transformed itself into the Trade Union Unity League in 1929, embracing the dual unionism it had originally rejected.

There is no such thing as “independence” in the class struggle. Workers either embrace the ideas of the socialist movement, remain totally mired in the ideas of the ruling class which dominate in capitalist societies or most frequently float somewhere in between. Calling to replace socialist leadership of the labor movement with the leadership of an “independent” rank and file is tantamount to abandoning the fight for socialism altogether. What was needed was not “non-socialist” leadership, but rather “non-Stalinist” leadership.

The Meaning of the TUEL’s Legacy for Today’s Work

We cannot and should not copy the model of the TUEL as a formula. All considerations must be made in light of our current context and circumstances, though this affirmation must be the beginning and not the end of the conversation. So what are the lessons of the TUEL, and how does a consideration of our current circumstances inform drawing from the TUEL as a model?

Above all, the lesson we should take from the successes of the TUEL is the key role of the militant minority. And it is not enough to recognize the importance of a militant minority, we must set out to build and organize it. As we continue to engage in strike solidarity, support new organizing, and push back against conservative and bureaucratic leadership, we must maintain a focus on strengthening our own forces. There is always a danger of remaining a debating society without getting our hands dirty in the class struggle, but there is also a parallel and serious danger of being so engaged in trade union work that we lose ourselves as socialists.

Practically, this means prioritizing our internal work, including by strengthening existing labor branches and seeding new ones. The recent hiring of a DSA labor organizer is a great step in this direction.

Structure

The overall structure of the DSA’s labor work is rather haphazard; it has developed more sporadically than according to a specific plan. That being said, we are making tremendous progress, and many comrades are beginning to consider structural questions.

The TUEL’s tremendous success in 1922 was facilitated by the strong relationship between four internal bodies — its national leadership, its national publication, its industrial organizations, and its local organizations — all melded into one comprehensive whole.

In contrast, the national leadership of the DSA’s labor work is not tied organically to our local labor bodies or to DSA’s national and local industry groups. As it stands, DSA’s labor membership directly elects our national labor leadership, and neither local bodies nor industrial organizations elect delegates.

This is not to say that the national leadership has been doing a poor job; in fact, the opposite is true. National leadership has helped to lead fantastic campaigns. But hard work cannot replace the value of structural integration between the local, industrial, and national leadership.

Additionally, we have no national DSA labor conference, but only informal quarterly meetings. A national conference should be called with local labor branches sending delegates, and the national leadership should be elected on this basis, although probably not on the same formula as the TUEL’s industrial secretaries. A conference allows for a greater degree of discussion leading up to elections, clear proposals to be articulated, the opportunity to sharpen a national strategy, and better integration between national, industrial, and local. The bi-annual Labor Notes conferences have shown the tremendous power of bringing radical militants together, but ours must go beyond Labor Notes as a conference that is explicitly socialist and focused on developing both our internal and external work.

Of course, for the organization as a whole, the DSA already has a national convention — our supreme decision-making body — which weighs in on labor and all other issues. A DSA labor conference would not replace or supersede the existing DSA-wide structure; rather, the labor conference would be able to go into greater detail on specific tasks within the labor movement and place well-developed labor proposals before DSA’s national conventions.

Politics and Membership

Perhaps the largest difference between the Communist Party-TUEL relationship and DSA’s work today is the structure of political membership and participation. The Communist Party had strict membership requirements and a narrower political ideology, while DSA has loose membership requirements and a more inclusive web of political ideologies.

The TUEL could not have succeeded in engaging workers if every worker needed to join the Communist Party to participate; a degree of independence provided space to engage wider layers. There are far lower barriers to radical militants joining DSA, and therefore it is not clear that we should create a separate non-DSA sister entity like the TUEL. Certainly, most of our campaigns and work, such as DSA’s industry groups, should be and already are open to a broader layer of militants. But there are a large number of youth and workers open to socialism and willing to join — or at least work in cooperation — with DSA bodies, so no new organization is necessary.

Publications

The Labor Herald was one of the main organizing tools of the TUEL. The publication was key for reaching wider sections of workers, educating comrades on labor developments, and promoting the strategy of the collective leadership.

I have been proud to contribute to Working Mass, our Massachusetts DSA labor publication, and am grateful for the support that many comrades and workers have expressed for our work. But practically speaking, it would be far easier, more sustainable, and further reaching to put out one quality national labor publication than several local labor publications. I do see a value to local DSA labor publications, but they should be sub-blogs of a national publication.

Such a publication must balance the twin tasks of remaining grounded in the issues facing today’s class struggle, and the task of fighting for a socialist labor movement. This means avoiding the twin dangers of being a socialist journal totally removed from, and therefore uninteresting to, workers, and the parallel danger of focusing exclusively on worker issues at the expense of a truly socialist position. At Working Mass we have tried to walk this balance.

Campaigns

We are already engaged in a multitude of campaigns in the labor movement, especially new organizing, pushing for renewed labor militancy, reform caucus work, and pushing unions toward a break with the corporate Democrats. Strengthening our structures will do a great deal to systematize and maximize these efforts.

In general, our work will develop from cheerleading workers’ struggle to pushing unions toward concrete reforms, militant campaigns, and anti-corporate politics, to backing reform leadership and finally to running DSA members themselves in leadership elections.

In the last period, it was the field of labor politics in which the largest layer of union workers engaged with radical ideas and fought for left-wing positions within their unions. In practically every local there were supporters of Bernie Sanders’ 2016 and 2020 campaigns self-organizing for their union to endorse Sanders. Having served on the leadership team of Massachusetts Labor for Bernie in the 2020 campaign, I can tell you that we suffered from a lack of organization and would have benefited tremendously from a pre-existing, well-organized structure. In the next period, organizing unions toward working-class politics has the potential to drive the clearest and most favorable division between the fighting-democratic and conservative-bureaucratic elements of the labor movement.

In the field of worker organizing, the two clear campaigns are new organizing and pushing existing unions toward militant strike action. We should assist every organizing campaign we can, and have a key role to play as the militant minority. But it is the established unions, not the militant minority, which have the resources capable of reaching the millions of workers required to rebuild a powerful labor movement. It is crucial that we place clear demands on the leadership of established unions to invest the resources necessary to expand the labor movement.

While the issues of amalgamation and industrial unionism are not fully resolved, they may not be the crucial campaigns for our work that they were for the TUEL. However, it is worth considering whether movements like the graduate workers would be better off in one national union rather than spread throughout several national unions. But even if this was answered in the affirmative, it is probably not the most important campaign.

The question of independent unions also deserves further consideration — and potentially differs from that of the TUEL. While we should absolutely fight for radical militancy within the AFL-CIO unions and other established unions, much of the best new organizing is taking place either outside the established unions or nominally within them, as with Starbucks baristas organizing under Workers United, but led by the workers. Certainly, we should back the campaigns of UE, Amazon Labor Union, and other independent union campaigns. Without abandoning a general orientation toward the AFL-CIO, it may — or may not — be the case that establishing our own union could be helpful in select cases where the already established unions simply will not run campaigns. These questions deserve further consideration — ideally at a DSA labor conference.

Conclusion: Learn from the TUEL

If we accept the TUEL’s philosophy that the militant minority is the key to the success of the labor movement, then we must prioritize strengthening our own internal structures in order to maximize our impact. The centralization of DSA’s labor work, facilitated by a national conference and a national publication, will maximize our ability to engage with the wider labor movement. From this position of strength, we will be better able to support new organizing and labor strikes, push unions towards militancy and away from corporate politics, oppose and replace conservative-bureaucratic leadership, and reach millions of American workers with a clear socialist strategy for worker power.

All DSA labor activists should study the publications of the TUEL. In my opinion, first-hand sources are generally better than historical reviews, which are almost always morphed by the political leanings of their authors.

Here are a few places to start:

The Principles and Program of the Trade Union Education League – Foster, 1922

A Year of the League – Krumbein, 1923

William F. Dunn Speach at AFL 1923 Convention – Dunn, 1923

Lenin and the Trade Union Movement – Lozovsky, 1924

Organize the Unorganized – Foster, 1926

Strike Strategy – Foster, 1926

For More:

Labor Herald archive

Labor Herald pamphlets archive

Henry De Groot is the Managing Editor of Working Mass, a member of the Boston DSA Labor Working Group, and an organizer with Massachusetts Drivers United.

The views expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not represent the official position of Working Mass.